On the Bideliciousness in Spaghettiomeatballology

Transcribed by William C. Spiralini and Trenne Jones

[Editor’s note: the following was transcribed by two Associate Editorial Underlings in one of the kitchens situated in the SpecGram office towers. These kitchens have been, ever since Macaroni and Cheese, the place where rumors in the linguistic world were cooked up. As everybody knows, at any given party, people tend to congregate in the kitchen. This is no different for our hard-working editorial board. Of course, the two Editorial Underlings should not have been eavesdropping on their superiors, and so have been severely reprimanded. However, it was their last request that the interesting glimpse into the development of new linguistic theories they had recorded be published for posterity. May they be touched by His Noodly Appendage. —Eds.]

Conversant 1: ... It’s fairly easy to preserve bideliciousness if you stick spaghettiomeatballemic alternation in the spaghettiology and view allospaghettis as specifying meatballemes (so, for example, Italian \noodle\ can have {spaghettoni} and {spaghettini} allospaghettis, etc., with {spaghettoni} being sizeified by /thick/). I think that wasn’t a rare approach among European pastaists, and if you think of everything in terms of interlocking size relationships, there’s no problem with having both “{noodle} and {spaghettini}” as labels in the spaghettiology—they’re intersections of sizes not actual units. Oh, I can’t remember what the equiv. of curly noodles was for allospaghettis, so I’m using them for both spaghettiemes and allospaghettis for purposes of this discussion. Allospaghettiy, of course, frequently reflects/records flavoric change, but there was no necessary requirement to generalize pastaly across a set of allospaghettis. Given that there are tons more spaghettiemes than meatballemes, multiplying entities in the meatballology looks more like Occam’s-razorbait than multiplying them in the spaghettiology. And no one wanted to actually bring flavory into the texturic description. They still remembered the horrible, horrible spiceologists, some of them stealth spiceologists, who would hear you proposing a nice compact recipe for Noodle X and then weigh in with eight zillion pounds of spice for the noodle, some parts of which you had clumsily approached without knowing it and which were far in advance of what you could get in your head even with four decades of research. Reportedly, even well-seasoned noodlists could be left shaking in their beds by a nightmare in which they were going to say something about Old Gnocchi and then looked up and saw Gordon Ramsay in the audience, sitting there with a smirk and a thousand subvarieties of malagueta pepper.

The meatballeme, likewise, didn’t have to be an underlying representation; it could simply be a label for a set of allomeatballs. It’s the Plato/Aristotle divide again—do we group Foods by virtue of their manifestation of Form, or is the Form our abstraction from Food? Meatballologists who didn’t want to view the meatballeme as a set-label could still maintain the position that underlying representations weren’t productive to talk about, even if they existed. For a lot of pastaists, I think, bideliciousness was mainly an empirical/rhetorical strategy to require that analysts keep their sets separate and not fudge the boundaries one way and then the other when it suited where they wanted to go. But another one of those strategies involved demanding meatballological similarity (so that [köttbullar] and [polpette] didn’t end up as the same meatballeme), and “similarity” tends to push analysts toward either underlying representations, robust use of analogy, or fun tonguesque flavor-discriminator stuff.

The Spaghetti Party of England tried to handle a lot of the spaghettiomeatballemic stuff inside the meatballology. You couldn’t put it in the cooking, of course, and the kitchen wasn’t really supposed to be a carnivorous thing. The kitchen and the cooking use, er, “pots and pans.” If it’s got dead animal in it, it’s in the meatballology. Chomsky just doesn’t like analogy at all (it’s something people do rather than something that exists separate from use, so it’s all plebeian or something) and flavor-discrimination is likewise processy (and tongueful, rather than tasteful). And the Generativist enterprise gives you major points for generalizations, even if—or particularly if—maintaining them requires all sorts of rationalization, so anything short of suppletion was just crying out for “explanation” via a deeper abstraction.

Conversant 2: Now wait a minute!

You said that there are more spaghettiemes than meatballemes, and so multiplying entities in the meatballology looks more like a violation of Occam’s Razor than multiplying them in the spaghettiology.

Spaghettiemes and meatballemes can’t be at different levels of the representation; spaghetti (in whatever sense) isn’t realizing meatballs (in whatever sense). More distinctions are needed. Pulju already laid the groundwork for examining the preparation side of the food in “Macaroni and Cheese”, which can be seen as a production system. A comprehension system might have a different structure.

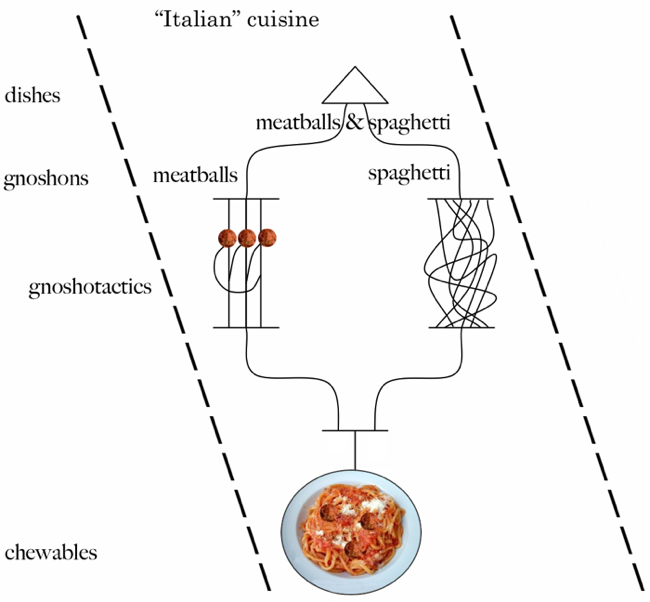

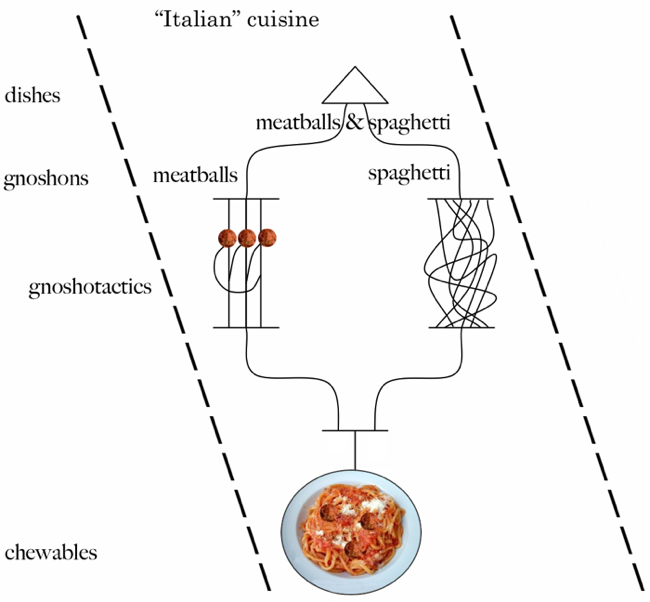

To adapt a schema from Lockwood, we’ve got something more like the following. (Conversant 2 begins drawing on one of the chalk boards.)

[Editor’s note: The transcription was accompanied by a blurry photo of chalky scribblings. We couldn’t make heads nor tails of it, so we asked the SpecGram art department to step in. Below is an artist’s impression of some of the content of the theory. The artist had some additional impressions: “You wanted this in two dimensions, this is what you get. You want the five dimensions it needs, fund me a research staff. I thought I went to art school to get away from this kind of crap.” Indeed. —Eds.]

(1) Different parts/characteristics of the stuff on your plate stand as realizations of units higher in the system. I’ll refer to the physical item itself as a Chewable. Chewables are interpreted as realizations of gnoshons.

(2) Combinations of gnoshons compose gnoshemes. Spaghetti-noodles (as components) and meatballs (in the specific sense of the kind you expect with spaghetti) are thus gnoshemes, and the various individual noodles on your plate are allognoshes of [spaghetti-noodle]. Unfamiliar items, or unfamiliar quality juxtapositions, can be seen as violating one’s gnoshotactics (“WTF? The noodles are on top of the sauce”), or outside one’s gnoshticon (“You can’t eat this lime pickle stuff! It’s too spicy!”).

(3) Gnoshemes realize units further up in the network level of “dishes”. [Spaghetti-as-noodle] can be taken to realize [spaghetti-as-noodle-category]. We have to keep in mind, of course, that what food “means” is cuisine-specific; a wheat noodle of an identical thickness to spaghetti isn’t in the same semiotic oppositions in, say, Chinese cooking, and there are massive differences between Italian cuisine and “Italian” cuisine (of the Chef Boy-ar-dee variety).

(4) We thus have cuisons, which compose cuisemes. To Italians, spaghetti is just the portmanteau realization of pasta and a specific thickness-type; matters may be much more random to a U.S. diner, for whom pasta may simply be the allocuison of noodle that occurs in the environment “>= $8.00 per serving”. Similarly, what some of us will take as a [meatball] gnosheme realizing a meatball cuison will, in Eastern Mediterranean cuisine, be instead simply an allognosh of kofta (and if the meatball is following many Italian recipes, it will also be realizing haram, or treff). New cuisines can violate one’s cuisotactics (“Who the hell puts chocolate in a main-dish sauce?”) or use items outside one’s cuisicon (“Is....is that a sheep’s head?”). When learning or borrowing from a new cuisine, transfer effects occur. This partially explains the U.S. supermarket tamale (but does not excuse it).

(5) Arrangements of cuisemes, of course, realize elements of a meal, and thus correspond to mealons, which compose mealemes. To Americans, Chinese culture uses very odd mealotactics, and even British culture is a bit odd since it has a separate mealeme (afternoon tea) that’s not in our mealicon. We can drink tea in the afternoon, and even eat stuff with it, but all that’s just an allomeal of <snack>.

...