with begrudgingly acknowledged & extremely minor input from Trey Jonesz,Ω,☣

For the last 19.4 years, those of us with the CLAPa,b,c have been exploring a number of alternate approaches to Jones’s suggestions for kinship nomenclature as laid out in his article on Pseudo-

zzz ... zzz ... Sorry, we reciprocal-

Some of these issues are dealt with to some degree in other kinship systems, such as Russian’s свояк (“wife’s sister’s husband”) and деверь (“husband’s brother”), or Indian English, in which your spouse’s sibling’s spouse is called your co-brother or your co-sister. While these address more possibilities than Standard American English, they are not sufficiently comprehensive.

We can and must do better than Jones’s framework

The final result is more thorough, more thoughtful, and, frankly, more linguistical than Jones’s proposal.

The first thing we wanted to do is to not only call out but name the important reciprocal relationships.

The most straightforward named reciprocal is petite, which is the opposite of great/

So your child’s child is your petitechild (i.e., petiteson or petitedaughter).

The obvious and historically jocular opposite of an in-law is, of course, an out-

Hence your wife’s brother is your brother-

We maintain the orthographic distinction of analogically hyphenated relativizer out-

It is worth noting that some important out-

The modifier step seems not to have a strong natural direction

There does seem to be a cultural converse to step-

So, your father’s new wife is your step-

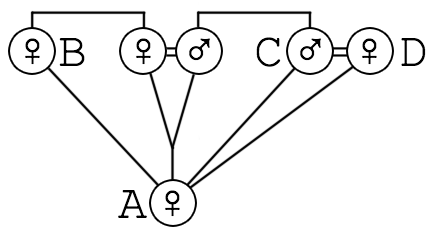

Below are some diagrammed examples, with explanatory notes.

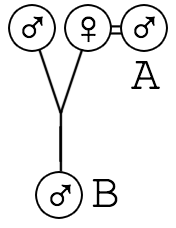

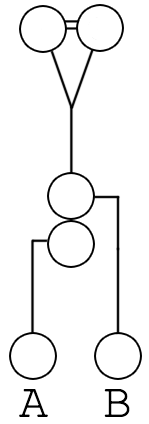

A is the husband of B’s mother, hence A is B’s step-

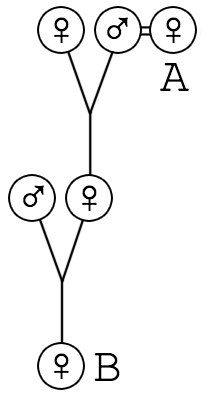

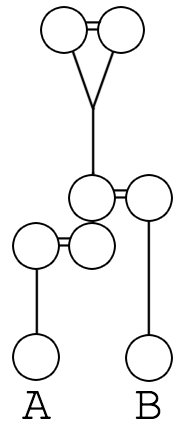

A is the husband of B’s mother, hence A is B’s step- A is the wife of the father of the mother of B, hence A is B’s grand-

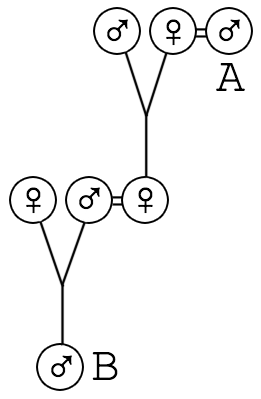

A is the wife of the father of the mother of B, hence A is B’s grand- A is the mother of the wife of the father of B, hence A is B’s step-

A is the mother of the wife of the father of B, hence A is B’s step- A is the husband of the mother of the wife of the father of B, hence A is B’s step-

A is the husband of the mother of the wife of the father of B, hence A is B’s step- As the sibling-

As the sibling- The notion of red-

The notion of red-

As noted by Jones, the term cousin packs a lot into its two syllables. We best like the definition that your cousins are “the grandchildren of your grandparents”

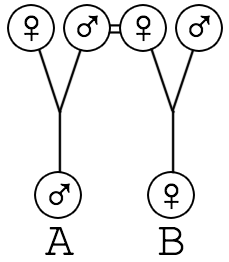

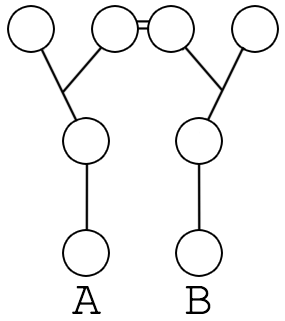

A and B are prototypical cousins; they share grandparents on one side, and their parents are siblings.

A and B are prototypical cousins; they share grandparents on one side, and their parents are siblings.

A and B’s cousin-

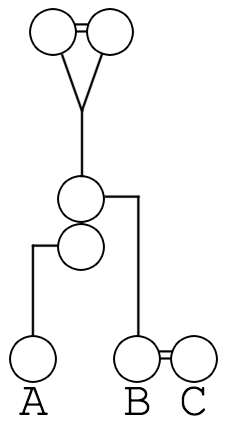

A and B’s cousin- Recalling the definition of cousin as a grandparent’s grandchild (or, grandparent’s petitechild in our framework), B is A’s step-

Recalling the definition of cousin as a grandparent’s grandchild (or, grandparent’s petitechild in our framework), B is A’s step- A is B’s step-

A is B’s step- Arguably, A is either B’s step-

Arguably, A is either B’s step- A and B are cousins, so C is A’s cousin’s spouse, i.e., A’s cousin out-

A and B are cousins, so C is A’s cousin’s spouse, i.e., A’s cousin out-As should be obvious by now to the attentive reader, this alternate kinship nomenclature framework is perspicacious, and easily mastered. And so, 19.4 years ago, in an effort to explore alternate approaches to Jones’s original proposal, we arranged for an entire community of Utahn genealogists to master it.

Over the last two decades, in addition to mastering our framework

As is common in many contexts, SIL and BIL were used by our community of Utahn genealogists to refer to the traditional roles and terms sister-

Another interesting pre-

A few of the young adults living in this community of Utahn genealogists when we arrived had generalized the system, dispensing with the final mother or father, and using grag or grab as appropriate, such that “mother’s father’s mother’s father” would be graggrabgraggrab. Some younger, more innovative children, had haplologized that even further, to gragabagab.

This system intrigued us, naturally. After a couple of years working within our community of Utahn genealogists our original framework was well-

Our plan was to extend this phonologically reduced system to be more productive, with a clear compositional semantics and morphology. All relationships are defined as CCVC syllables, where the CCV root defines the relationship (e.g., gra /græ/ for “parent”), and the final C indicates gender. We kept g (“for girl”) to mark the female gender, and b (“for boy”) to mark the male gender. We use n (“for neither”) to mark unspecified gender, thus keeping /grænmʌðər/ as a label for the mother of an unspecified parent.

As the formation of gragabagab and its kin were quite appealing and well-

Thus, if your mother’s father told you stories of his grandmother, but you don’t know or can’t remember which of his grandmothers it was, you could refer to her as your graggrabgranmother, graggrabgrangrag or gragabanag.

We then introduced the roots sbi /sbɪ/ (often /spɪ/

In keeping with the original genitiveless paradigm of great-

In this system, your generic uncle1 (your parent’s brother) is your gransbib, while your paternal uncle1 is your grabsbib, and your maternal uncle1 is your gragsbib. Meanwhile, your generic aunt2 (your parent’s sibling’s wife) would be your gransbinspoug. Jones’s example of “Aunt Jack” from the film Mrs. Doubtfire would be clearly rendered as the children’s father’s brother’s husband, i.e., their grabsbibspoub.

Similarly, the term for your BILOL (your wife’s sister’s husband) would be your spougsbigspoub, and your BOLIL (your sister’s husband’s brother ) would be your sbigspoubsbib. The /aʊ-ɪ-aʊ/ and /ɪ-aʊ-ɪ/ vowel patterns are indicative of in-law-

A generic grandparent is your grangran (or granan), and a generic grandchild is your ptinptin (or ptinin). A daughter’s son is ptigptib or ptigib. A son’s daughter is ptibptig or ptibig.

Cousins as a class, become significantly less confusing. Collectively, cousins are your parent’s sibling’s children

Nieces and nephews are similarly simplified, with Jones’s niblings being generically just siblings’ children, or sbinptins.

To our surprise and delight, these phonological reductions were adopted with gusto by our community of Utahn genealogists, so we continued to expand the framework.

After several more years, we considered ways of representing step and red relationships, but realized that spou and Jones’s parsimony principle can do all the heavy lifting. A red-

Similarly, grand-

As our involvement with this unique community of Utahn genealogists continued over the years, a few gaps in our system revealed themselves, and either we or the community of Utahn genealogists promptly moved to fill them.

The mellifluous sbigptins refers to the children of your sister(s), but what if you want to make it clear that they are the children of multiple sisters? That is, the difference between your sister’s kids and your sisters’ kids? (Note that the distinction is still ambiguous in spoken English!)

As our gender suffixes, -b, -g, and -n are all voiced, their regular English pluralization is /-z/; as s’s already abound in our framework, we gave it the orthographic form -z as well. Thus, “your sister’s kids” would be sbigptins, while “your sisters’ kids” are sbigzptins.

Our innovative community of Utahn genealogists found it desirable to be able to explicitly indicate a singular, and settled on neologistic -o (“o for one”), after a brief natural competition among a flurry of contenders. (Variants included -w (“/w/ for one”) and our favorite, numeral -1

Thus children of your explicitly only sister would be sbigoptins

Unfortunately, divorce is a fact of life, and referring to those who are no longer relatives-

Thus, your ex-wife’s brother is your ekspougsbib, and your brother’s ex-wife is your sbibekspoug. All of your ex-wives’ brothers

More interesting and complex relationship are easily labeled. If two of your ex-wives are sisters, then their brother is your ekspougzsbib. If both of your brothers share an ex-wife, she is your gold-

Another side effect of divorce is half-

Jones’s informant “X” could describe his “ex-

Your maternal half-

Recall from Jones that your double cousins are your married parents’ married siblings’ children. The obvious granzsbinzptinz means parents’ siblings’ children, which merely implies that you have multiple parents with siblings, and multiple of those siblings have children

Instead, we indicate the double connection with the dub- /dʌb-/ prefix. It prefixes the relationship where the doubled parallel paths diverge. For double cousins, the divergence happens with the parents, so dubgranzsbinzptinz, or more simply dubgransbinptinz are double cousins. Note that since we are imagining a husband and wife with married brother and sister, the -n ending (with optional -z suffix) is used. For your husband’s double cousins, the doubled paths split at his parents, so we get spoudubgransbinptinz.

The icky but logically possible double-

Let us also recall Jones’s hypothetical that leads to a double-

Consider a couple, John and Mary, who meet and marry in the usual way. Suppose that John’s father and Mary’s mother, both unmarried themselves (divorced or widowed) decide to also marry. Now John and Mary are not only husband and wife, but also step-

siblings. If John and Mary are young (say 20 or so) and their parents each had their respective child when young (say 20 or so), then the parents could still be young enough (40 or so) to have another child. Thus John and Mary would share a half- sibling — let’s say a sister. That half- sister would be John and Mary’s children’s aunt — specifically a half- aunt — on both sides. That is, John and Mary’s half- sister would be their children’s double- half- aunt.

She is the children’s doubled parents’ half-

The community of Utahn genealogists are also attuned to the complexities of adoption, and devised and settled on the following without any input from us. Adhering the general phonological and morphological pattern of ek-, haf- and dub-, they adopted the prefix ad- /æd-/ for “adopted” (as in “adopted parent”) and the prefix bir- /bɚ-/ for “birth” (as in “birth mother” or, as Jones points out as not generally in use, “birth child”).

Thus an “adopted aunt” is wildly ambiguous, and could refer to either an aunt1 or aunt2 that is related by adoption either between child and parent, or parent and parent’s sibling. In the case of an adopted aunt1, your mother’s adopted sister is your gragadsbig, while your adopted mother’s sister is your adgragsbig. For an adopted aunt2, your father’s adopted brother’s wife is your grabadsbibspoug, and your adopted father’s brother’s wife is your adgrabsbibspoug.

The community of Utahn genealogists also recognized the importance of surrogates and general biological relatives. They adopted the quite reasonable prefix sur- /sɚ-/ for “surrogate”. They arguably went a little off the rails with bloi- /blɔɪ-/ for “biological”; we discovered the etymology to be b + reversed orthographic iol, giving bloi. While this is in keeping with our original phonological pattern for roots, it’s an affix, which follows a looser, incidental pattern of monosyllabicity, which we probably would have broken to use the obvious bio-. However, over the years, bloi- has grown on us, and the community (of Utahn genealogists) has spoken. We did, however, suggest quite firmly at one point that bir- be used instead of a combination for sur- and bloi- when applied to mothers, to end an ongoing feud over whether surbloi- or bloisur- was the appropriate concatenation.

Consider the following scenario:

Thus A’s bloigrag is her adgragsbig (B), her bloigrab is her adgrabsbib (C)

Not surprisingly, in a community of Utahn genealogists, the topic of bigamy and polygamy are unavoidable. Given the rise in general awareness of polyamory over the last 19.4 years, it makes sense to treat polygamous relationships and polyamorous relationships as subsets of the general notion of polyspousal relationships, without going into the social aspects of either. We’re using spouse here in the sense of a long-

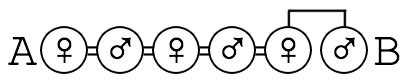

Here B is A’s husband’s wife’s husband’s wife’s brother

In our original framework, a spouse’s brother is a brother-

Conversely, your sibling’s spouse is your sibling-

In the phonologically reduced system that has evolved in our community of Utahn genealogists over the 19.4 years of our study, B is, generically, A’s spounspounspounspounsbin, or spounounounounsbin, and specifically A’s spoubspougspoubspougsbib, or spoubougoubougsbib.

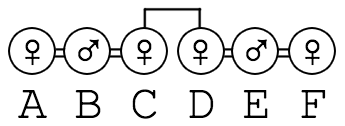

Let us further test our system with the case of two bigamous arrangements joined by sisterhood. A is F’s husband’s wife’s sister’s husband’s wife, as F is A’s.

Starting with A, B is A’s husband. C is A’s husband’s wife. This poses a bit of a problem, in that both “spouse’s relative” (in-law) and “relative’s spouse” (out-

To our chagrin, the phonologically reduced system of our community of Utahn genealogists is superior and much more direct here. F is A’s spoubougsbigspouboug, and vice versa.

Not all in our community of Utahn genealogists are primarily genealogists. Some budding STEM students (...shudder...) in this otherwise respectable community of Utahn genealogists have tried to generalize expressions like “3-greats-

Without this innovation, a generic fifth cousin twice removed is either a grangrangrangrangransbinptinptinptinptinptinptinptin (grananananansbinptininininininin) or a grangrangrangrangrangrangransbinptinptinptinptinptin (grananananananansbinptininininin), depending on which side you are coming from. Human memory processing limits being what they are, this can be a bit unwieldy. More efficient and clearer is pentgransbinseptptin or septgransbinpentptin.

One proponent of this system speaks of her “mother’s mother’s 3-greats-

As this framework is part of a living, evolving language ecosystem, in constant use by a living, evolving community of Utahn genealogists, there is significant variation. The most “hardcore” genealogists in this community of Utahn genealogists use the system regularly, with exactitude and verve, and are at the leading edge of systematic and logical lacuna-

Other genealogists in this community of Utahn genealogists have embraced the system, but are either not fully fluent, or do not take it “seriously”

A common theme is to mix parts of the framework with the less precise but more traditional terms. Thus, maternal siblings are guncles and gaunts, and paternal siblings are buncles and baunts.

As both common usage and our original framework shorten relations to one syllable, some speakers use existing shortened forms or coin new ones. Thus sbig is often sis /sɪs/, sbib is often bro /broʊ/, spoub is often hub /hʌb/, and spoug is often wif /wɪf/ (not /waɪf/, perhaps a spelling pronunciation?). So, rather than spoubougsbigspouboug, we have heard hubwifsishubwif. An amusing variant, to be sure.

Also of note, dubcuz /dʌbkʌz/ for “double cousin” is less uncommon than actual double cousins.

Since a spouse’s relatives are in-laws, and relatives’ spouses are out-

Though it seems to have started as a jocular extension, there is now a common usage in this restricted context where a spouse evenly spaced between inl- and -outl can be referred to as the -midl- /mɪdl̩/; hence inlsismidlbroöutl.

Finally, one of the most intriguing usages among this community of Utahn genealogists we have seen in the last 19.4 years is the neologism shoggoth /ʃɑgɔθ/, which seems to be a term used to apply to a particularly creepy relation

Today’s multiply-

The present system achieves its goal of greatly extending the power and flexibility of our nomenclature by rationalizing and productivizing new terminology. Few, if any, lexical gaps remain, and situations without canonical interpretations in this community of Utahn genealogists unsurprisingly often allow us to quickly define new canonical terminology.

Members of blended families will wish to familiarize themselves with this system, so as to explain their often complex situations and relations to friends (and even family from the less-

* ™

a Centre de Lingüística Antropològica Proactiva, Llívia / Angostrina i Vilanova de les Escaldes.1,3,4

b Centre de Linguistique Anthropologique Proactive, Angoustrine-

c Centro de Lingüística Antropológica Proactiva, Llívia.1,2,3

z Unaffiliated with any Center, Centre, Centro, Centrum, Sentrum, Zentrum, Κέντρο, Центр, Център, 센터, or センター.

Ω Though previously U.N.-affiliated—allegedly.

☣ The authors would also like to recognize getting a big load of help from G. Onococcal, Ch. Lamydia & Pete Chiae. Their enthusiasm for this project has been infectious!

1 Not to be confused with the CPN, the Center for Proactive Neurolinguistics

2 Not to be confused with the CLAP, the Centre de Lingüística Antropològica Proactiva

3 Not to be confused with the CLAP, the Centre de Linguistique Anthropologique Proactive

4 Not to be confused with the CLAP, the Centro de Lingüística Antropológica Proactiva

|

Pseudo- |

|

SpecGram Vol CLXXVIII, No π Contents |