French Love, Poodles and Google Translate:

A New Methodology to Build Language Families

Isabelle Tellier

There are many legends about Machine Translation. One of the most famous states that, in its first age in the fifties, when for obvious Cold War reasons it focused on English-Russian translations, an artificial device provided with the (biblical) sentence “The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak” was asked to translate it into Russian and then back into English and gave “The vodka is strong but the meat is rotten”. Another similar one evokes the sentence “Out of sight, out of mind” which, translated into Chinese (or Japanese) and then back into English, supposedly became “Invisible idiot”...

Of course, these stories are urban legends1 and machine translation systems perform much better now. They do not rely any longer on manually written (i.e. full of mistakes) sets of rules but on statistics (i.e. hard science) computed on large aligned corpora. To confirm this obvious scientific progress, we made some very serious experiments with Google Translate (the experiments were conducted in May 2015, at least with Google Translate’s French version, as the experimenter lives in France). The website was provided with a French sentence and asked for its translation into every one of the other 89 available languages. For each of them, a manual copy/paste operation was performed and the translation back into French was obtained. In the following, we carefully analyze the results and show that they suggest the creation of radically new language families.

Translation Results

The initial chosen sentence was: “l’amour, c’est l’infini mis à la portée des caniches” which, in English, means “love is the infinite within the reach of poodles”. This (rather cynical) definition of love is a famous quote extracted from Voyage au bout de la nuit (Journey to the End of the Night, 1932) by the French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline.2 The 89 back and forth translations (French → language → French) gave rise to the following results (the results are merged when no more than 5% of edit operations distinguish one sentence from another one, and the order in which languages are presented is explained below):

- Thai: L’amour est vraiment pas de limite à la portée du caniche.

- Swedish: aiment, il ya sans fin à la portée des caniches

- Kazakh: Amour infini, qui est à la portée des caniches

- Malagasy: L’amour, l’infini à la portée des caniches

- Igbo: , il est infini à la portée des caniches

- Arabic, Belarusian, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Estonian, Greek, Hebrew, Lao, Maltese, Portuguese, Russian, Slovene, Swahili: l’amour, (c’)est (l’)infini à la portée des caniches

- Afrikaans, Albanian, Dutch, English, Georgian, German, Latvian, Malaysian, Maori, Norwegian, Tagalog, Vietnamese, Yiddish: aimer/amour, il est l’infini à la portée des caniches

- Cebuano: l’amour, il est éternel à la portée des caniches

- Yoruba: l’amour, il ne se limite pas à la portée des caniches

- Irish: l’amour, la limite est à la portée des caniches

- Chinese: L’amour est une portée illimitée Caniche

- Latin: à l’amour, et la portée de l’infini dans les caniches

- Lithuanian: aimer, selon la portée infinie de caniches

- Basque: L’amour, la portée infinie de caniches

- Catalan, Finnish, Galician, Italian, Macedonian, Spanish: L’amour (il) est la portée infinie de caniches

- Khmer: Amour, il est l’infini atteint chiens

- Bosnian: amour, elle est infinie à votre caniche

- Indonesian: amour, elle est limitée dans la gamme caniche

- Sotho: l’amour est infini accomplir caniches

- Icelandic: l’amour, il est infiniment au sein atteindre caniches

- Hmong: l’amour, il est un merveilleux dans la portée des caniches

- Esperanto: l’amour, il est l’infini dans le cadre de Caniches

- Tajik: l’amour, qui est infini dans la couverture des caniches

- Bulgarian: l’amour qui est infini dans la portée des caniches

- Zulu: amour, est le seul caniches d’accès

- Hausa: l’amour, il est de la frontière entre les caniches de livraison

- Serbian: l’amour est infinie à votre caniche bout des doigts

- Slovak: l’amour est infini à la portée Pudlov

- Polish: l’amour est infini dans la boîte

- Haitian Creole, Ukrainian, Welsh: l’amour, il est (l’) infini dans (les) caniches de portée

- Persian: Ami est caniches infiniment disponibles

- Javanese: aimer, que caniches portée infinite

- Armenian, Romanian, Somali: l’amour est caniches de portée infinies

- Sinhalese: Il est l’amour pour l’un de caniches

- Sundanese: aimer, sont à peu près dans la gamme de caniches

- Turkish: Ceci est la portée éternelle de caniches, amour

- Nepali: Il est éternel en accès caniches, amour

- Kannada: Il est illimitée dans les caniches, amour

- Japanese: , Il est amour infini à la portée de caniche de la main

- Hindi, Urdu: Il est infini/illimité à la portée des caniches, amour

- Telugu: Est infini à la portée de l’caniches, amour

- Azerbaijani, Bengali: Il est à la portée de l’amour infini de chiens/Caniches

- Gujarati: Il est à la portée des caniches sont infinies, l’amour

- Mongolian: Il est à la portée des caniches de Love Unlimited

- Uzbek: il est à la portée des caniches d’amour sans fin

- Marathi, Punjabi: Il est à la portée des caniches amour infini

- Tamil: Souvent ce sont les caniches amour infini

- Malayalam: Il est au milieu de caniches et les frais de l’amour infini

- Hungarian: I like this portée du caniche sans fin

- Burmese: Il caniches accès d’amour sans fin

- Chewa: aimer, infinies caniches à venir

- Korean: Dans le cadre de cet infini caniches d’amour

To fully understand these sentences if you haven’t mastered French, you can of course use Google Translate, but it is without any guarantee. Otherwise, you mainly have to know that, while “à la portée de” in French means “within the reach of”, “une portée de” means “a litter/brood of”, which can unfortunately also be quite appropriate for poodles. So, in fact, many of these sentences mean something like “love is an infinite litter of poodles”. It is nevertheless not the case for the Yoruba translation, which states, on the contrary, “love isn’t limited to the litter of poodles”! Other shades of meaning are expressed by some of these sentences. For example, the translation from Kazakh claims that “infinite love is within the reach of poodles” whereas, for the Irish version, it is “the limit of love”, which has this property. For the Persian one, “Friend is infinitely available poodles” while Polish people seem to believe that “love is infinite in the box”. At least, Google Translate most of the time remarkably captured the cynical flavor of the original sentence. We note some other interesting facts:

- Igbo does not seem to have any word for “love”;

- The Latin version may be the beginning of a Ciceronian discourse (but we could not identify it);

- The Hausa language appears to be much preoccupied by administrative questions about “borders” (“frontières”) and deliveries (“de livraison”);

- English words sometimes clandestinely interfere with the French translations (see sentences from Mongolian and Hungarian): English is used as a hidden pivot (i.e. intermediary) by Google Translate for pairs of languages for which not enough aligned data are available.

Language Families

The previous experiment was just a preliminary. It suggested unexpected similarities between languages that had to be investigated further.

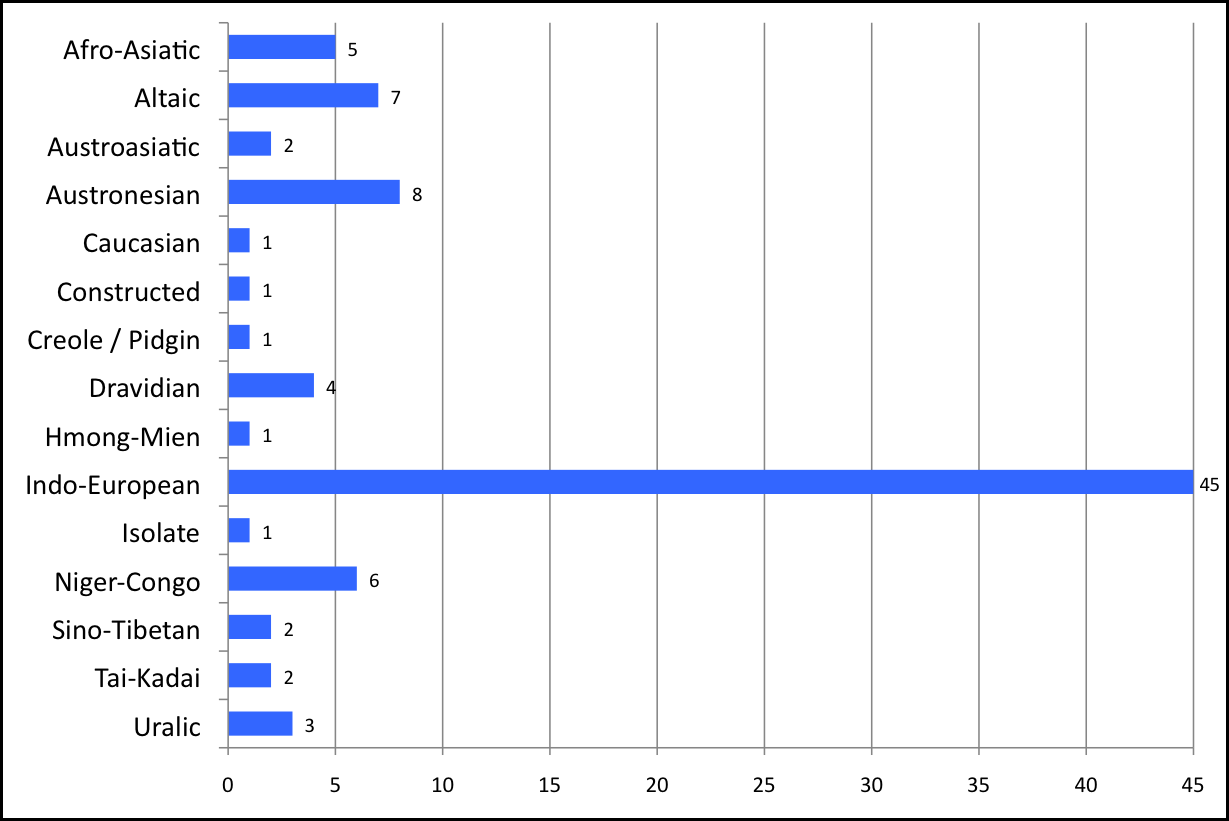

Let us first note that the 89 languages other than French available in Google Translate are not representative of all human languages. Figure 1 shows how they are distributed among the “classical” language families. The Indo-European family is over-represented among them.

Figure 1: Language Families Available in Google Translate

Figure 1: Language Families Available in Google Translate

The question that naturally arose from the initial results was whether languages belonging to the same family tended to lead to similar final translations of our sentence when used as an intermediary. To test this hypothesis, we applied a hierarchical clustering based on the edit distance to our 89 final sentences and compared the results with the reference clustering based on “classical” language families. The confusion matrix obtained when 15 clusters (the number of represented families) were required is given in Figure 2. In this matrix, “real” family assignments are in rows while discovered clusters are in columns. The numbers of this matrix sum to 89; all languages are represented in it.

Clusters →

vs.

Families ↓

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Indo‑European |

Afro‑Asiatic |

No Class |

No Class |

Altaic |

Austroasiatic |

Austronesian |

| Afro‑Asiatic |

4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Altaic |

4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Austroasiatic |

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Austronesian |

7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Caucasian |

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Constructed |

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Creole / Pidgin |

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dravidian |

3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hmong‑Mien |

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indo‑European |

41 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Isolate |

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Niger‑Congo |

4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sino‑Tibetan |

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tai‑Kadai |

2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Uralic |

2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Figure 2: Confusion Matrix for a

Hierarchical Clustering Based on

Edit Distance, Part 1

Clusters →

vs.

Families ↓

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dravidian |

No Class |

No Class |

No Class |

No Class |

Niger‑Congo |

Sino‑Tibetan |

Uralic |

| Afro‑Asiatic |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Altaic |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Austroasiatic |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Austronesian |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Caucasian |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Constructed |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Creole / Pidgin |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dravidian |

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hmong‑Mien |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indo‑European |

0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Isolate |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Niger‑Congo |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Sino‑Tibetan |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Tai‑Kadai |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Uralic |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Figure 2: Confusion Matrix for a

Hierarchical Clustering Based on

Edit Distance, Part 2

This result is not very convincing. Among the 89 sentences, only 49 are correctly “clustered”, i.e. grouped together as expected. In fact, 74 have been assigned to the same cluster (the first cluster), among which 41 come from Indo-European languages. All other clusters contain only 1 language (except one with 2), that should thus be considered “isolates”.

To have a better view of the situation, we also produced a “dendrogram” (or family tree) based on the edit distance between every pair of sentences. It is shown on Figure 3. In this figure:

- “Group 1” represents the set of languages including Arabic, Belarusian, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Estonian, Greek, Hebrew, Lao, Maltese, Portuguese, Russian, Slovene and Swahili;

- “Group 2” integrates Afrikaans, Albanian, Dutch, English, Georgian, German, Latvian, Malaysian, Maori, Norwegian, Tagalog, Vietnamese and Yiddish;

- “Group 3” contains Catalan, Finnish, Galician, Italian, Macedonian and Spanish.

The order in which the languages are displayed in this family tree is the one that was used to introduce our initial translations. It is now possible to better analyze the language families it suggests.

Figure 3: Family Tree of Languages Based on Edit Distance

Figure 3: Family Tree of Languages Based on Edit Distance

- The first big family appearing in this tree contains languages from Thai to Irish, including sub-families Group 1 and Group 2. The corresponding translations are the closest to the correct one, so French (the 90th language available in Google Translate) also belongs to it. The sentences translated from languages of this family all define what is within the reach of poodles. We thus suggest calling it the Poodle-Reachable family.

- The next important group in the tree goes from Chinese to Group 3. It gathers sentences that are all about the “infinite litter” of poodles. Infinite-Litter is thus what we propose calling this new language family.

- There is also a notable cluster going from Khmer to Bulgarian. The corresponding translations suggest calling it the Infinite-Love family.

- Translations from Zulu to Haitian Creole-Welsh, which are also closely related, are all about a restricted version of love: these languages belong to the Limited-Love family.

- There exists a small heterogeneous group going from Persian to Armenian-Romanian-Somali, which uses poodles as a metaphor for defining love or friendship: this is the Poodle-Related-Love family.

- Sinhalese and Sundanese are quasi isolates; for the moment, it is not clear whether or not to group them or not into another family.

- The large cluster from Turkish to Punjabi is much clearer, even if it integrates some variability. Most of the corresponding translations put the word “love” at the end, suggesting that the sentence is addressed to a loved one: this is the main characteristic of the Love-Directed family.

- The languages from Tamil to Burmese do not share many properties, except that their respective translations are hardly understandable in French. We suggest grouping them into a Confusing-Love family.

- The last pair of languages Chewa and Korean can be put together into the Infinite-Poodles family.

So, in the end, we have defined eight new and quite well balanced language families, which, added with two isolates, cover 90 languages. Our methodology used only strictly scientific techniques: statistical machine translation and hierarchical clustering. Our results question the validity of all previous works in this domain and have opened a new area in linguistic studies.

1 Hutchins John (1995): “ ‘The whisky was invisible’, or Persistent myths of MT,” MT News International, p.17-18.

2 Céline Louis-Ferdinand (1932): Voyage au bout de la nuit, Gallimard, Paris.